FMC and the Two-Engine Dilemma: When the Present Devours the Future

Guest Author: Christian Pereira, Agribusiness Strategist at Bizup Strategy, specializing in growth strategies and M&A.

18 February 2026, New Delhi: If FMC had a pipeline, a growing biologicals platform, and world-class professionals and I have no doubt about the caliber of those who have been and still are there, why couldn’t it reinvent itself in time?

I want to bring a different angle today. Less about what happened in the market and more about what happens inside companies when they need to transition from today’s business to tomorrow’s. And what any crop protection company can learn from this.

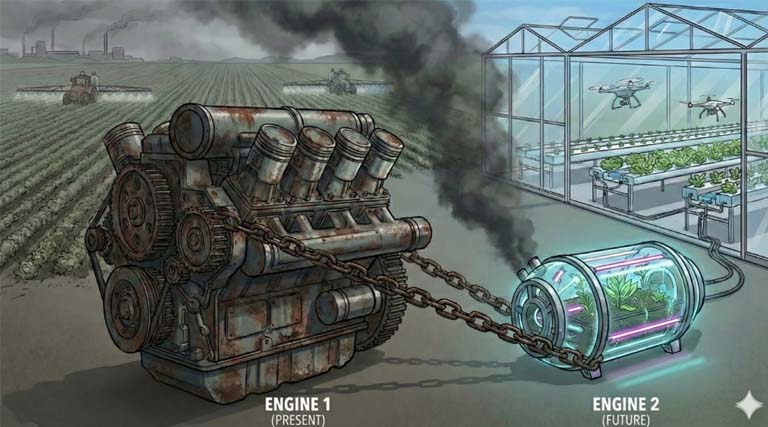

The answer, in my view, lies in a concept by Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble, professors at Dartmouth: the Engine 1 and Engine 2 framework. The FMC case is probably the best lesson agribusiness has ever produced on what happens when the engine of the present devours the engine of the future.

Two Engines, One Company

The logic is elegant. Every company pursuing sustainable growth needs to run two engines simultaneously. Engine 1 is the core business — the revenue machine, optimized for efficiency and predictability. Engine 2 is the innovation initiative that will generate tomorrow’s revenue — one that requires experimentation, tolerance for failure, and protection from the pressure for immediate results.

The problem? Engine 1 was designed to reject Engine 2.

Not out of ill will. By the system’s own logic. Every dollar invested in Engine 2 is a dollar that “could” be optimizing Engine 1. And when Engine 1 starts showing signs of exhaustion, the natural temptation is to double down on it — exactly the opposite of what should be done.

FMC’s Engine 1: Brilliant and Dangerous

Rynaxypyr (chlorantraniliprole) was for years the most successful insecticide in the global market. At its peak, over $1 billion in revenue, 25% of total sales, with margins that sustained the entire structure.

But there’s a detail that makes this story even more telling: FMC did not develop Rynaxypyr. It acquired it from DuPont in 2017, as part of the divestitures required by the Dow-DuPont merger. In other words, FMC bought a ready-made Engine 1.

And here’s the crucial point: when you buy an Engine 1 at the peak of the cycle, the urgency to build an Engine 2 should be even greater, not less.

Because you don’t have the organic capability that created that blockbuster. You don’t have the historical molecule pipeline or the R&D culture that generated the original innovation. You have the result, but not the process. And without the process, the next breakthrough molecule doesn’t just appear.

So what was the mistake? Letting the entire organization gravitate around an engine it didn’t build and failing to invest with the necessary urgency in building its own.

Commercial structure, incentive systems, decision-making culture, capital allocation — everything shaped by Rynaxypyr. FMC invested heavily in strategies to extend the life of that engine:

1. Process patents to protect the 16 synthesis steps of the molecule

2. Approximately 60 licensing agreements including five with global multinationals across more than 19 countries

3. Advanced formulations (Elevest, Vantacor) to maintain differentiation

None of these actions were wrong. But they were all Engine 1 actions, they defend what exists, they don’t create what comes next.

Defending Engine 1 is not a growth strategy. It’s a survival strategy. There’s an enormous difference between the two.

The Engine 2 That Didn’t Accelerate

FMC didn’t ignore innovation. In 2025, new active ingredients (fluindapyr, Isoflex, Dodhylex) reached $200 million, a 54% growth. The biologicals platform has been growing consistently and represents roughly 5% of revenue.

So why didn’t it work?

Because Engine 2 isn’t just about having a pipeline. It’s about speed to scale, team autonomy, and crucially, investment timing. Not to mention the strategy execution challenges that large companies face. Engine 2 needs to be accelerated while Engine 1 is still strong and not when it starts to fail.

The math is unforgiving.

Rynaxypyr closed 2025 at just over $800 million, a significant decline from the peak. With hundreds of generics registered in China and prices up to 80% below branded products, erosion will accelerate in 2026. New active ingredients added $70 million in one year. But the net balance remains negative.

It’s like trying to fill a bathtub with the drain open.

The Pharma Lesson That Agribusiness Keeps Ignoring

The pharmaceutical industry lived through this dilemma between 2011 and 2016. Pfizer faced the expiration of Lipitor, $13 billion in annual sales and its internal Engine 2 couldn’t compensate.

What did Pfizer do? It bought Engine 2 from others.

The acquisition of Wyeth for $68 billion was essentially that: buying the engine of the future because the internal one didn’t grow fast enough.

And here’s the irony of the FMC case: in 2017, it made a major acquisition and but bought Engine 1, not Engine 2. It bought Rynaxypyr from DuPont at the peak of the patent cycle. Pfizer bought future. FMC bought present. And when the present expired, there was no future at scale to take over.

FMC today is in an even more vulnerable position. With $3.5 billion in net debt and 4.1x EBITDA leverage, it lacks the firepower to buy innovation. Instead of buying Engine 2, it may become someone else’s Engine 2.

Why Engine 1 Always Wins Internally

In my experience, I see three mechanisms that systematically suffocate Engine 2. All three are visible in the FMC case:

1. Resource competition. Every R&D dollar for biologicals competed with Rynaxypyr defense. When revenue dropped, the reaction was to protect Engine 1, exactly the opposite of what theory recommends.

2. Metrics that punish innovation. Engine 1 measures margin and ROI. Engine 2 needs to measure registration speed and adoption rate. Same yardstick, unfair result.

3. Culture of predictability. Quarterly guidance and EBITDA targets are perfect for Engine 1 and toxic for Engine 2. Innovation demands tolerance for failure and long horizons.

Worth reflecting: in your company, are mature business metrics also suffocating growth initiatives?

Biologicals: An Engine 2 With Potential, But No Time

FMC’s biologicals platform is probably the most attractive asset for a potential acquirer. With a target of $2 billion by 2033, it’s a legitimate Engine 2.

However, even at that pace, it will take years to reach Rynaxypyr’s scale. And FMC doesn’t have that time. Free cash flow in 2025: negative $165 million.

The classic Engine 2 irony: it needs time and protection to mature, but a collapsing Engine 1 eliminates exactly those conditions.

Had FMC accelerated its investment in biologicals three or four years earlier, when Rynaxypyr still generated abundant cash — the story could be different. For whoever acquires the company, this platform may be the most valuable asset.

What This Means for You

If you lead a crop protection company — chemicals, biologicals, seeds, distribution — consider four questions:

1. What is your Rynaxypyr? The product or channel that sustains your revenue. What is the real lifespan of that engine? Not the one you’d like, but the one the market is determining.

2. Does your Engine 2 have real autonomy? Dedicated team, its own metrics, different reporting line. If you measure biologicals with the yardstick of mature chemicals, they won’t survive.

3. Are you investing now or waiting for the crisis? The window is when the present still generates cash. FMC waited too long.

4. Do you need to buy Engine 2? When the internal engine doesn’t grow at the necessary speed, M&A becomes a strategic tool. Biologicals startups, data platforms, application technologies.

The Real Dilemma

FMC didn’t fail because of a lack of intelligence or resources.

It failed because the system that made Rynaxypyr extraordinary was the same one that prevented the next bet from reaching scale. Worse: it bought a ready-made Engine 1 and didn’t build Engine 2 with the urgency that demanded.

BASF is separating its agricultural division. Corteva is splitting crop protection and seeds. These are belated attempts to give Engine 2 the conditions it never had within the integrated structure.

The question isn’t whether your business will face this dilemma. It’s when. And when it comes, will you have an Engine 2 ready?

(The views expressed in this article are those of the author and are shared to encourage industry dialogue and perspective.)

Reference: Govindarajan, V. & Trimble, C. The Other Side of Innovation: Solving the Execution Challenge. Harvard Business Review Press, 2010.

Also Read: France Becomes First Market to Approve Syngenta’s X-Terra Hybrid Wheat

Global Agriculture is an independent international media platform covering agri-business, policy, technology, and sustainability. For editorial collaborations, thought leadership, and strategic communications, write to pr@global-agriculture.com